At rush hour at Paris’s Saint-Lazare station, activists, including a civil servant in a government ministry and a former climate-change protester, were out canvassing for an unusual would-be candidate for French president.

Their choice, Sandrine Rousseau, is a figurehead of the French #MeToo movement against sexual violence, an economist and university vice-chancellor and promises a new form of “punk ecology”.

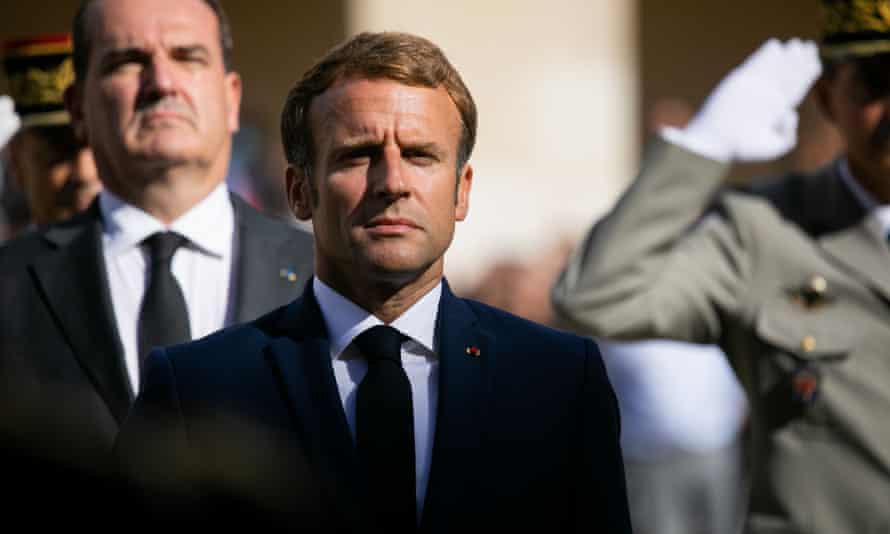

“People want change, they don’t want the same old faces,” said Camille Borgetto, a French woman in her 40s, in response to polls showing the presidential runoff in April will pit the centrist Emmanuel Macron against the far-right Marine Le Pen in a repeat of the last election.

This month France enters its fraught pre-election season to choose the final presidential candidates. Rousseau, who defines herself as an “eco-feminist”, is running in the Green party’s primary race, open to all voters, including foreign residents, who sign up before Sunday. Elsewhere, political wrangling could stretch on all autumn, particularly in Nicolas Sarkozy’s traditional right party, Les Républicains, which believes it could win the presidential but has not chosen its candidate.

Macron will not announce his candidacy for a second term until early next year. But his approval ratings have grown this summer over his handling of the latest phase of the Covid crisis, pushing up vaccination levels to among the highest in Europe by introducing a health pass, despite the small but regular street protests every Saturday.

Meanwhile, Le Pen, who runs her far-right National Rally party from the top down and appointed herself candidate with no internal competition, will launch her campaign at a party conference this weekend. She disclosed a taster of her manifesto this week, including nationalising motorways to save drivers money on toll charges, as well privatising national TV and radio in order to cut the licence fee – designed to appeal to voters who distrust of the media – and limits on who can apply for French nationality.

The left’s challenge is to harness voters’ concerns. Climate change is one of French voters’ main worries, but despite the Greens increasing their urban vote and taking control of cities including Lyon, Strasbourg and Bordeaux last year, the party did not win any regions this year. Its most high-profile candidate in the primary, Yannick Jadot, a member of European parliament, is polling at about 10% in the presidential race.

The Paris mayor, Anne Hidalgo, could officially announce this weekend that she will run for the Socialist party. Her personal story is being used to present her as close to the people, to counter Macron’s image as haughty. Born in Spain, she arrived in France at two, where she grew up on a housing estate near Lyon, gaining French nationality in her teens. She says she wants to “pacify” political debate in a society marked by the gilets jaunes street protests and polarisation.

“What you notice is she’s starting to talk about incomes, people’s everyday issues, the republican concept of France, social justice and social rising in society – how many generations do you need as the child of a worker to earn more than your parents?” said Michel Gelly-Perbellini, a Socialist activist in Paris. “I believe that’s something people care about in France, not just Islam and the security topics that are flooding the TV channels.”

Hidalgo’s candidacy would be confirmed by an internal primary race. But she faces the major hurdle of a divided left. An Ipsos poll this month placed her in fifth position at 9%, behind the possible Green candidate Jadot, on 10%, and with the leftist Jean-Luc Mélenchon on 8%. There will also be a Communist party candidate running; a former Socialist minister, Arnaud Montebourg, also wants to run.

“The problem today on the French left is that there is not one dominant party,” said Rémi Lefebvre, professor of political science at Lille university. “There’s no party that has broken out from the rest to become the ‘useful vote’ on the left.”

Like the Socialists, Les Républicains did well in regional elections in June, but the historic abstention rate of more than 65% made it impossible to predict whether those parties could make a comeback at presidential level.

“The paradox is the classic left and right parties did well in local elections, but they haven’t found cohesion nationally,” said Lefebvre. “There’s a decoupling of local political life and national political life. Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen’s parties are very weak at a local level, yet they are the ones with a chance of reaching the final of the presidential race.”

Valérie Pécresse, a former budget minister under Sarkozy and head of the wealthy Île-de-France region surrounding Paris, is the favourite to win any primary race held by Les Républicains, far ahead of the former Brexit negotiator, Michel Barnier. Pécresse has defined herself as “two-thirds Angela Merkel and one-third Margaret Thatcher”, which she says means being tough and economy-focused while building consensus. Another candidate, Xavier Bertrand, the regional head of north-eastern Hauts-de-France, has begun his own presidential campaign and is polling well, but refusing to take part in a primary. It could take all autumn and winter to resolve.

The journalist and TV debate-show figure Éric Zemmour could also launch a presidential bid this autumn. Labelled France’s most famous far-right ideologue, and with criminal convictions for racial and religious hate speech, he is polling at 5-7%. He could eat into the scores of both the traditional right and the far-right Le Pen.

Without the final lineup of candidates, Macron currently remains favourite in the polls. He has held on to his solid voter base from the last election, which is crucial for the first round of a presidential race.

Adrien Broche, a political consultant for the pollster Viavoice, said its research this month showed Macron scored well among voters on credibility and competence in leading France in a crisis, but lower on his personal connection to ordinary people. “Technical competence is his strength; his weakness is the issue of whether he is close to the French people and their concerns. That’s where the opposition is expected to challenge him,” he said.