Sitting in the living room of her Berlin apartment, Sanaa* watches proudly as her one-year-old daughter clings to the edge of a coffee table and hauls herself to her feet. Siba* squeals with delight, then drops back down with a giggle. Being a single mother is hard work, but filled with daily rewards. Sanaa, who fled the Syrian war, is just thankful for the chance to raise a child.

Experts are warning that children such as Siba could turn into a stateless generation. Though the infant was born in Berlin after her mother arrived from Damascus, there is no automatic German citizenship. And under Syrian law, a child can only inherit nationality from its father. As a single mother, Sanaa was well aware that Siba would be stateless.

“There is no paper for Siba in Syria. Because it’s the law, you don’t have any relations before you are married. People have boyfriends but it’s secret,” Sanaa says. “We just grow up and this is the rule. We didn’t know that the women in other countries can give their nationality [to their children], or we didn’t care because we would get married and the child would have a nationality.”

Now, conflict and displacement have left 25% of Syrian refugee households fatherless, according to the UN. Most European countries, including Germany, tie nationality to the “right of blood” and none automatically grants citizenship to all children born on their soil. Although international treaties oblige states to ensure every child’s right to a nationality, European governments are failing to do so, or even to recognise that children are being born stateless at all.

The UN released a report this month calling for global action on child statelessness. “In the short time that children get to be children, statelessness can set in stone grave problems that will haunt them throughout their childhoods and sentence them to a life of discrimination, frustration and despair,” said the UN high commissioner for refugees, António Guterres.

At least 10 million people globally do not have citizenship of any country, according to the UN. Without nationality, stateless people cannot vote and can find it difficult or impossible to gain access to healthcare, education and employment.

The UN estimates that there are 680,000 stateless people in Europe, though experts say the figure is likely to be much higher. There are hundreds of thousands of Russian-speaking minorities in Latvia and Estonia who became “non-citizens” following the fall of the Soviet Union. There are thousands of Roma in Italy and the Balkans left stateless in large part due to the breakup of Yugoslavia.

The experiences of these long-term stateless people highlight the dismal fate that awaits Syrian children if their legal nationality is not resolved.

* * *

Beyond Rome’s frenzied centre, the quiet outer suburb of Monte Mario is home to a “nomad camp” where many of the residents are stateless. There is an uneasy calm after the police shut down the camp’s weekly flea market. It’s a regular flashpoint in tense relations between Roma residents and the municipality.

Roma began migrating to Italy from the former Yugoslavia in the 1980s when, following the death of dictator Josip Tito, a rise in Yugoslav nationalism saw them become increasingly marginalised. The numbers of displaced Roma moving to Italy swelled again in the 90s during the Bosnian war as Europe faced another massive wave of displacement.

Like refugees the world over, many fled their homeland without papers. The documents they did carry identified them as citizens of a country (Yugoslavia) that no longer existed. In Italy, they settled in informal camps where they were segregated from mainstream Italian society and often continued to live undocumented in a country that does not grant citizenship necessarily to people who were born there or live there. As a result they cannot legally work, graduate from school or open bank accounts, and access to healthcare is limited.

“We were born and grew up in Italy. And what do we get? Nothing,” says Davide, who was brought up in the Monte Mario camp. “Not even papers. Where are our rights? We have no rights. We are no people with no nation.”

Humica was born in the former Yugoslavia but has lived most of her life in Italy. Her two children and five grandchildren were born and raised in the Monte Mario camp. “I am Italian in the sense that I was born here,” says Humica’s son, Dean.

“But society doesn’t recognise us as Italian and neither does the law,” his mother adds.

Without papers, Dean cannot work legally. He makes a living doing removals and collecting scrap. But he does not have licences for these activities. And now, he says, the scrapyard has put up sign saying it will no longer do business with Roma people.

As for many stateless people around the world, the problem for the Roma is both a legal failing and one of entrenched discrimination. “Anti-Roma racism is a really powerful force in Europe,” says Adam Weiss, legal director of the European Roma Rights Centre. “I think the most visible way in which the Roma are excluded is refusal to recognise them as members of national communities.”

Being stateless and undocumented also reinforces this exclusion. Lacking a proper education or the right to work forces many to look for employment outside the law, in turn fuelling accusations that the Roma are a criminal minority who refuse to integrate.

And the situation is not limited to Italy. Exclusion from bureaucratic processes means there are still large numbers of Roma at risk of statelessness in the ex-Yugoslav states, as well as in Ukraine and Bulgaria.

* * *

The 1954 UN convention relating to the status of stateless persons was drawn up in the aftermath of the second world war when statelessness in Europe was rife. Most EU countries have ratified the convention, obliging them to offer the stateless basic rights and protection in much the same way as refugees. But while refugee rights are recognised internationally, with asylum procedures to determine who is entitled to such protection, only a handful of European countries have formal procedures to recognise the stateless.

Michel*, 35, was one of the first people to benefit from the UK’s statelessness determination procedure after it was introduced in 2013. An orphan, he was brought up in a madrasa – an Islamic religious school – in Ivory Coast. His earliest memories are of begging on the street. At the age of 14 he was trafficked to Senegal to work on a plantation. He escaped as a young man and a friend helped him reach Europe.

In the living room of his terraced house with views of the Yorkshire moors, he explains that he did not know he was stateless until researching ways to prevent his deportation following the failure of his asylum claim. With no knowledge of where he was born, or who his parents were, Michel realised he had no legal claim to Ivorian nationality.

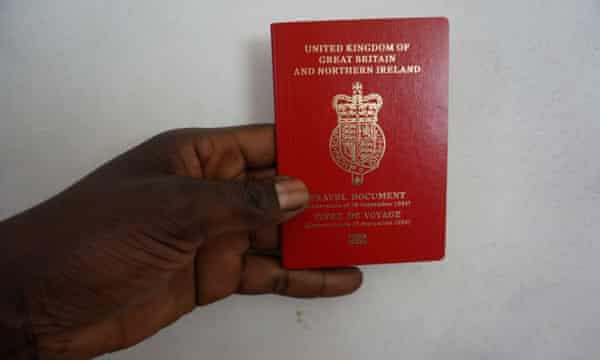

Michel’s first application to be recognised as stateless was rejected. After the Liverpool Law Clinic (LLC) stepped in to challenge the decision, he got his first ID – a stateless travel document – in 2014, 15 years after first arriving in the UK. “My life has changed dramatically,” he says. “Before I got my papers, all my thinking was very low. Stress. It’s like I’ve been reborn. I can see coming just good things. I’m very happy.”

Michel now plans to study. But he is one of the lucky ones. Sarah Woodhouse, from the LLC, says that as of spring this year, only about 20 of the approximately 700 people who had attempted the procedure since it was introduced had been recognised as stateless.

Rather than simply determining that a person is stateless and therefore has a right to protection, the procedure aims to identify any possible country to which the undocumented might be deported.

“It’s not really a procedure for helping people who are stateless,” says Pierre Makhlouf, a lawyer with Bail for Immigration Detainees. “It’s actually a procedure to identify those who cannot be removed. The rules look at both whether or not you have had status in any other country and been present in any other country, and expects you to establish that you won’t be accepted by another country.”

Gábor Gyulai, an expert on statelessness with the Hungarian Helsinki Committee and president of the European Network on Statelessness steering committee, says this additional criterion violates the 1954 statelessness convention. Nonetheless, the UK’s acknowledgment of statelessness represented real progress. “Certainly the UK procedure was a very important step,” says Gyulai. “I remember a few years ago there seemed to be very little appetite to introduce such a procedure.”

Yet recognition of statelessness remains fraught with contradictions that are often Kafkaesque. With very few exceptions, statelessness determination procedures put the burden of proof on applicants, who must show that they are not citizens of any country to which they have habitual or family ties. But few embassies will issue documents confirming that someone is not a citizen. The UK government even lists “current passport” among the documents sought to bolster a stateless application. And many such procedures are only open to people who are already legally resident – even though statelessness itself can be a barrier to residency.

Italy has one of Europe’s oldest statelessness determination procedures. But Nando Sigona, a sociologist at Birmingham University who has studied statelessness among Italy’s Roma for many years, says he has not heard of a single Roma person being recognised through the country’s official administrative route.

“It seems as if in the way the bureaucratic process has been designed they have some idea of the deserving stateless, and those like the Roma don’t fit in and as a result cannot apply – the abject stateless,” Sigona says.

Humica has been formally recognised as stateless by the Italian authorities but only managed this through a complex and expensive judicial procedure. Since she got her papers four years ago, she has had the legal right to work in Italy. But she is still unemployed. “I wanted to be a normal person, to find a job, but things are just the same,” she says. “You’re not going to get a job if you live in the camp. Have you ever seen a Gypsy working alongside Italians?”

For Humica, the biggest advantage of being recognised as stateless is that she no longer fears the immigration authorities. Like many undocumented Roma, she has spent time in immigration detention.

Ibrahim* is an undocumented migrant who was held in immigration detention for three-and-a-half years in the UK. Having served six months of a 12-month prison sentence for using forged documents to work, Ibrahim expected to walk free, but instead he was loaded into a G4S van and driven to Dungavel House immigration removal centre in South Lanarkshire.

“When I arrived I saw the big walls. The barbed wire. I thought: this is prison again,” Ibrahim recalls. But he was wrong. Immigration detention turned out to be far worse. “In prison you count your days down. In immigration detention you count your days up and up. You don’t know when you will be released or deported.”

Born in Guinea to a Gambian mother and Guinean father, Ibrahim has lived in both countries but neither would recognise him as a citizen and issue the travel documents the British authorities needed to deport him. After two-and-a-half years, he was transferred to Colnbrook, the high security detention facility next to Heathrow. He had long since signed up for voluntary return but without a passport he was no closer to boarding a plane. Detention Action eventually found Ibrahim a solicitor, who successfully brought his case against the Home Office for unlawful detention.

Ibrahim is now “free” but stuck in a limbo of another kind. He has no legal residency and yet is unable to leave the UK. Not about to risk working illegally again, he fills his time volunteering as a cook and support worker for destitute refugees. His only hope is to prove that he is stateless.

* * *

Latvia also has a statelessness determination procedure. But the country denies that its almost 260,000 non-citizens are stateless. When Latvia became independent in 1990, only those who could trace their family’s presence on the territory to before Soviet occupation in 1940 were granted citizenship. The rest – more than 730,000 people accounting for almost a third of the population – were defined as non-citizens. They were allowed to remain in Latvia but without the right to vote.

Standing in front of the red and white stripes of the Latvian flag, Zoja Saulite recites the Latvian oath of allegiance. She reads from a crumpled piece of paper, stumbling over words in a language she has learned late in life. The 75-year-old grandmother smiles with relief as she finishes her declaration and sits down. After half a century living in Latvia, Zoja is now a Latvian citizen.

Back at home in Daugavpils, a city in the south-east of Latvia, and speaking more comfortably in her mother tongue of Russian, she explains why she decided to take the naturalisation test – a procedure she found arduous, having to repeat the language exam three times before passing. “I wanted everybody in the family to be a citizen,” she says. Her children now live in the UK. Without Latvian (and therefore EU) citizenship, she would need a visa to visit them.

About two-thirds of Latvia’s former non-citizens have died or emigrated, or gained Latvian nationality since the government lifted age restrictions on who could be naturalised in the 1990s. But approximately 12% of the Latvian population remain stateless. Although they now have most of the rights of Latvian citizens, they cannot vote and are barred from working in the civil service and some other professions, such as pharmacy.

Latvian identity, as defined by the state, is strongly tied to the Latvian language. But Russian is the main language in many towns and cities across the country. For non-citizens, many of whom are now pensioners, learning a new language often feels like an impossible task.

Valentina Pugachevska says she doesn’t speak Latvian well enough to pass the test. She was born in Belarus, but says Latvia is where she belongs. It’s where the 60-year-old spent her working life, raised her children, and where she wants to grow old. But her lack of nationality is painful. “It’s not written on my face that I’m a non-citizen, but whenever I have to pull out documents, I am ashamed,” she says, displaying the page in her ID where the word “alien” is printed next to her photo.

Latvia does admit there is a problem with the non-citizen status, which was only ever meant as a temporary fix designed to limit Soviet influence as the newly independent country found its feet. But over the past two decades, rather than helping to slowly “integrate” the non-citizen population, many people have been alienated by being forced to take a naturalisation test.

Sergei Kruks was born to Russian parents in Latvia in 1968. During the struggle for independence he was a radio presenter and vocal in his support of the pro-independence Latvian Popular Front. “We had many hopes for the future, but it ended abruptly in the first days of October [1991, when MPs decided not to grant citizenship to those who came to Latvia during the Soviet occupation]. Those I voted for decided not to grant people like me citizenship. It was a shock.” Kruks says the experience has caused ongoing psychological and emotional trauma.

The language exam would be a breeze for Kruks but he refuses to be naturalised, seeing the process as an expression of the state’s refusal to accept Russian speakers as an intrinsic part of Latvian society.

And it’s not just Latvian non-citizens who would rather remain stateless than conform to an identity imposed on them by the state. Antun Blazevic is a stateless Roma actor, playwright and poet who also goes by the stage name of Toni Zingaro – zingaro being the Italian slang for Roma, equivalent to “Gypsy” and generally regarded as a derogatory term. For Blazevic, it’s a badge of honour in the face of the common claim that Roma people refuse to integrate into Italian society. “The western world doesn’t want to integrate people,” Blazevic says. “They want assimilation.”

Blazevic – who was once arrested for occupying the Colosseum in Rome in protest at the death of a Tunisian refugee in Italian immigration detention – enjoys his statelessness as identifying him as everything and nothing. He has no plans to apply for Italian citizenship, rejecting the very idea of the nation state that defines who is worthy of rights and who is excluded. “What would I want with an Italian passport?’” he scoffs. “I am a citizen of the world!”

* * *

Back in Berlin, Siba is too young to have thought about her national identity. Sanaa says that in Syria, being a single mother would be impossible because of the social stigma. What she wasn’t expecting was the heavy-handed questioning about the identity of her child’s father that she was subjected to by the German authorities. But she did not name him, for reasons she chooses not to reveal.

Sanaa and Siba now have refugee status, and Siba has a travel document identifying her as a Syrian refugee, but the “Syrian” designation has no legal basis. Sanaa knows that Siba will not have the right to live in Syria unless a future government changes its nationality laws. In any case, she sees their future in Germany.

Since the conflict erupted in Syria nearly five years ago, her life has changed beyond recognition. When Sanaa first arrived in Germany she hated it. She found the people as cold as the weather and she felt alone, watching the destruction of her homeland from afar. She still misses Damascus but has grown to love Berlin. She is proud to be a single mother and happy her daughter will grow up in a society she sees as more free. This is home now. She has a wide circle of friends and Siba’s first words are emerging in German as well as Arabic.

In a few years, Sanaa plans to apply for German nationality, which Siba would benefit from too. But she will have to meet various criteria, including being able to support her family financially. Stateless campaigners argue that Siba’s citizenship should be automatic and her mother should not have to tread carefully to ensure this right.

As the latest UN report says, there are “straightforward legal and practical measures” that governments should put in place to prevent statelessness and “ensure that children’s very real connections to their countries are recognised through the grant of nationality”.

Compared with the legal complexity of recognising and granting rights to stateless adults, protecting children from being born stateless in Europe should be a relatively achievable goal. While some countries have not ratified international treaties to protect the stateless, all EU member states have acceded to the UN convention on the rights of the child, which obliges countries to grant nationality to children who would otherwise be born stateless.

Most countries go some way to enshrining these rights in domestic law. But conditions are often attached that are not in line with international treaties – meaning stateless children are only entitled to citizenship if, for example, their parents are legally resident in their country of birth. And in practice, the law is not often implemented. Italy’s citizenship law automatically grants citizenship to stateless children born on its soil, but insists on at least one parent being formally recognised as stateless before the child’s birth. This ignores children who cannot inherit their parents’ nationality, and the many stateless Roma parents who are completely undocumented.

But while Roma statelessness is deeply entwined with discrimination, Europe is currently experiencing a rush of goodwill towards Syrian refugees – and children in particular – which could inspire the kind of action on statelessness that has not been forthcoming for the Roma or Russian speakers of the Baltics.

“Because of the general understanding that Syrians are refugees, there is still a high level of solidarity throughout Europe,” says Gyulai. “These children are already extremely vulnerable and if they become stateless it will make their situation much worse – especially if there is no mechanism to officially perceive this statelessness and the rights attached to it. This is a test for the mechanisms to prevent statelessness and it’s a good opportunity for states to look at their practice and legislation.”

While studies have shown that the risk of statelessness among the children of Syrian refugees is widespread in Turkey and Lebanon, there has been no research into the scale of the problem in Europe. Moreover, the fact that children such as Siba are currently in the asylum system means that their parents will often not realise that they are stateless. But this largely invisible issue could have long-term consequences for them.

Acting now to prevent these children of Syrian refugees growing up stateless could head off the problems experienced by other stateless people in Europe. An absence of paperwork might have seemed a minor problem in the midst of the geopolitical upheavals of two decades ago, but it has become a barrier to integration that is harder and harder to solve. Meeting the immediate needs of refugees is one thing, but if governments fail to recognise the long-term impacts of statelessness, a new generation could grow up in limbo.

* Names have been changed

This article was supported by a fellowship from the French-American Foundation – United States. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the views of the French-American Foundation or its directors, employees or representatives.

• This article was amended on 16 March 2016. An earlier version said two-thirds of Lativia’s 730,000 non-citizens had gained nationality since the 1990s. Many of that two-thirds died or emigrated while non-citizens.