Coronavirus: The state had 21 million N95 masks stockpiled. All are expired.

As the coronavirus pandemic slammed into California and doctors and nurses sounded the alarm on a dire shortage of masks, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced the release of the state’s emergency stockpile of 21 million N95 respirators.

What he didn’t mention then: They are all expired.

Every one of the masks stored in the state’s climate-controlled warehouse in a secret location has surpassed its wear-by date. A California Department of Public Health news release this month indicated that only “some” masks are expired, but after repeated inquiries from The Chronicle, the agency acknowledged that the whole supply is outdated.

“All of the 21 million N95 respirator masks are expired but are usable per CDC guidelines,” the department said. “The masks have been stored in climate-controlled conditions that preserved their efficacy.”

The state has distributed millions of the expired masks to hospitals in the last few weeks. None of the hospitals contacted by The Chronicle is using them — yet.

Newsom said Saturday that “most” of the state cache’s masks had expired.

“We worked with the FDA to get approval, because of the cold storage and the fact that the equipment and masks were in very good order, to be able to distribute those masks,” he said at a news conference at the Bloom Energy factory in San Jose. “We’ll look to those expirations, we’ll look to repurposing and look to securing logistics around the world to what we need.”

What could limit the expired masks’ use in this pandemic is quite simple — an elastic band. The resilience of the band that holds the mask in place can wear over time and prevent a tight fit on the nurse or doctor wearing the mask.

The issue has raised questions about how the state’s emergency supplies, stored specifically for use in the event of a pandemic, could be expired. The state has not said how old the masks are, when they expired or why it has not replaced them.

The out-of-date equipment doesn’t surprise UC Berkeley infectious disease expert John Swartzberg.

“Our society was not prepared for a respiratory pandemic,” he said. “We could have been.”

John Balmes, a UCSF pulmonologist, said the expired masks still have effective filtering capacity.

“It would be nice to see the state purchasing new masks on a regular basis, but ... I think the expired masks should be distributed for protection of frontline health care workers to hospitals that are running out of non-expired N95s,” he said. “An expired N95 is very much more effective in protecting against SARS-CoV-2 infection than homemade cloth masks.”

UCSF Medical Center has received three shipments of expired masks from the state. The hospital moved them to storage, said spokeswoman Kristen Bole.

“We have received expired masks from the state, but we are not refurbishing them at this time,” she said. “At the current time, we have an adequate supply of new N95s to meet our needs, at least for the time being, so we are reserving the state masks for backup use.”

Bole said if those masks are needed down the line they will be inspected first and potentially refurbished to follow CDC guidelines. That likely would mean ensuring that the elastic is adequate to create a snug fit.

At Kaiser Permanente, medical staff are not currently using expired masks.

“We are providing our staff with the protective equipment that is aligned with the latest science and guidance from public health authorities,” said Karl Sonkin, a Kaiser spokesman. “We are not providing expired masks to our medical staff. We would do so only if every other possible source of masks was exhausted.”

The governor’s office did not respond to requests for comment, but Newsom has repeatedly stressed at press conferences that in addition to the state stockpile, California is receiving protective gear from the National Strategic Stockpile and private vendors.

On Saturday, the governor said the state has distributed 31.7 million N95 masks and secured another 101 million to be delivered soon. But during a three-month surge of coronavirus patients, California hospitals would need 200 million sets of personal protective gear, a set including masks, gloves and more, he warned.

“It gives you a magnitude of what we need and what we’re looking for,” Newsom said. “We’re dealing in the multimillions, hundreds of millions,” of personal protective equipment.

For more than a decade, after the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, emergency supply funding at federal and state facilities has dwindled.

In 2013, a group of federal advisory boards warned that continuing to underfund the Strategic National Stockpile would jeopardize its mission, which is to be prepared for major medical outbreaks.

As for the expired masks, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention created the guidelines for when they can be used and in which medical situations.

In early March, before shutdown orders and the full extent of the pandemic had emerged in California, the state department of health issued an order that the expired masks not be used when treating COVID-19 patients.

“These masks are approved for use only in limited, low-risk circumstances, thus relieving pressure on the supply chain of unexpired masks for health care providers caring for confirmed COVID-19 patients and other high-risk situations for infectious diseases,” the order said.

But with shortages and under emergency pandemic circumstances, there is latitude.

David Miller, research director for Service Employees International Union-United Healthcare Workers West, called it a “hierarchy ending in bandannas,” referring to the CDC’s approval of the use of scarves and bandannas to protect workers under the most dire circumstances.

“It’s a race to stay in front,” said Miller, whose union represents 97,000 hospital workers in California. “You don’t use expired masks until you have to.”

His union had been operating “paycheck to paycheck” — as member hospitals come within days of running out of masks, and small shipments of supplies keep them going a little longer. Last week, it became dire.

“We panicked, and we’re like, ‘Oh s—!’” Miller said. The labor association spent 48 hours calling leads and potential suppliers and finally found a distributor that had 39 million masks, and another supplier who said his company could produce 20 million more in a week. The union is connecting states, counties and health systems, including California, Santa Clara County, Kaiser and Sutter Health, so they can buy in bulk.

It shouldn’t take the unions to panic shop, he said.

“The level of unpreparedness is astounding,” Miller said of the expired masks. “You’re supposed to have a stockpile that works in a pandemic to keep people safe. It’s just maddening and mind-blowing.”

National Nurses United has filed more than 125 complaints with Occupational Safety and Health Administration offices in 16 states, charging hospitals with failing to provide safe workplaces.

In the trenches, expired or unexpired means little to some nurses and doctors.

“It’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard,” said Mawata Kamara, an ICU nurse at a private Northern California hospital who has been forced to use the same N95 mask for two weeks. “I’ll take an expired mask any day of the week. There are no germs on them.”

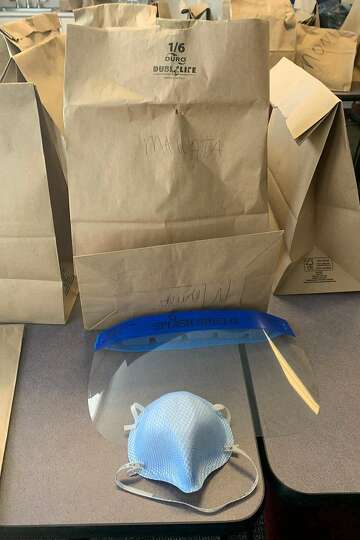

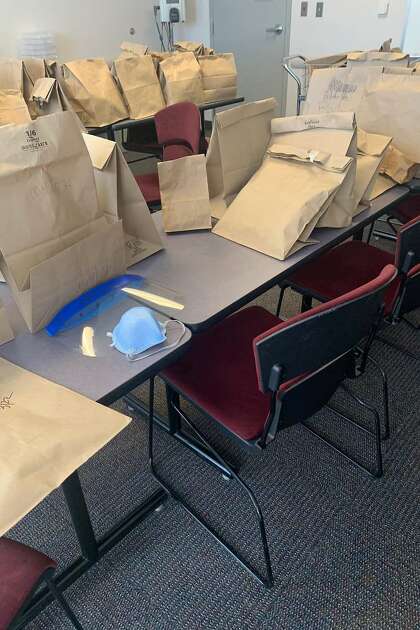

In between visits to a COVID-19-positive patient at the hospital and other potential coronavirus patients, she stores her sole mask in a paper bag with her name on it so it doesn’t accidentally get taken by a colleague. A photo she shared with The Chronicle shows dozens of paper bags with nurses’ names written on them sitting on a classroom table just off Kamara’s unit holding the hard-to-find equipment.

She also works as an emergency department bedside nurse at the public San Leandro Hospital, where she gets one N95 mask per shift. When she comes home from a shift, she has created a decontamination station in her Tracy garage with a change of clothes and cleaners for one last sweep before greeting her 4-year-old daughter Alma.

“It’s exhausting,” Kamara said. “I’m just getting anxiety attacks dealing with all the gear.”

Matthias Gafni is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: matthias.gafni@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @mgafni

Editor’s note: Reference to a warning from state regulators to Marin General Hospital (now called MarinHealth Medical Center), cited by National Nurses United, has been removed. Regulators notified MarinHealth of a complaint containing an alegation of a violation of state safety regulations.