“Australia is the only continent on the planet, other than Antarctica, that does not have high-speed rail,” says the former managing director of Hitachi Consulting, Gary Fisher.

Hitachi has been involved in high-speed rail since it was introduced into Japan in the 1960s and Fisher has been one of the principal enthusiasts for an Australian project.

Australian politicians have been talking about it for almost as long, yet high-speed rail (above 250km/h) or even fast rail (above 200km/h) still seem a distant pipe dream.

The University of Wollongong academic Philip Laird calculates $125m in today’s dollars has been spent on high speed rail investigations, but not one kilometre of corridor has been reserved.

“High-speed rail has often been promised, often before elections (a Melbourne-Geelong service is the latest one) only to vanish afterwards,” he says.

A lack of vision and political will, short-termism, genuine concerns about viability and vested interests have all played a part in creating stumbling blocks.

But now there is a renewed push, this time by state governments as well as by a few in federal parliament. It’s driven by a new concern that congestion and the cost of retrofitting major cities with mass transport is crippling Australia’s competitiveness and making cities unliveable.

“One of the problems with high-speed rail, for too long it was seen as a method of getting from Sydney to Melbourne as an alternative to flying,” says the Liberal MP John Alexander, who has chaired several inquiries into the future of cities and is now an evangelist for high-speed rail.

“The real problem we are trying to address is housing supply and affordability,” he says.

“Because we have had no plan of settlement, we have had an imbalance of settlement. It has resulted in congestion in our major cities and the second highest cost of housing in the world.”

Alexander has seen the impacts first hand. His electorate of Bennelong, centred on Epping in Sydney’s middle ring, is feeling the pressure as the city has expanded.

Roads into the city are clogged, trains are full and there have been big increases in housing density around railway stations. The median price of a suburban bungalow has risen to $1.5m and houses often sell for close to $3m.

With high-speed rail, he says, “Gosford, the southern highlands and Wollongong could be 15 minutes from the centre of Sydney and Newcastle, Goulburn and Nowra 30 minutes”.

“You are uplifting the value of that land enormously to compete with one of the most expensive markets in the world.

“You can reduce the number of cars coming into Sydney and you can strategically rebalance our settlement.”

The Very Fast Train that never arrived

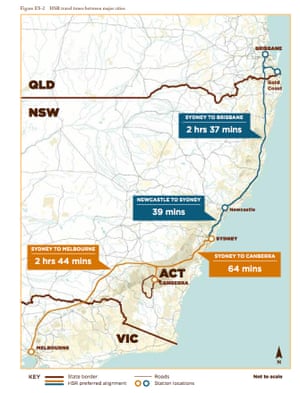

In the past most of the focus has been on a Sydney – Canberra – Melbourne line.

In the early 1980s, Paul Wild, the head of the CSIRO, returned from a trip to Japan inspired by his travel on the Shinkansen, and urged the federal government to consider what was then known as the Very Fast Train linking the three capitals.

The prime minister, Bob Hawke, was hooked and set the ball rolling. The scheme was backed by BHP, Elders IXL, Kumagai Gumi and TNT, who proposed that the project would be funded entirely by the private sector.

Over objections from the bureaucracy, the VFT joint venture proceeded through a feasibility study but was abandoned in 1991, primarily because it failed to secure tax changes from the federal government that it claimed would have made it financially viable.

The deregulation of the airline industry, which has slashed airfares, also helped undermine the economics of Melbourne to Sydney high-speed rail. Sydney to Melbourne is now the world’s second busiest domestic air route, with 54,519 flights a year and the airlines have become highly protective of this lucrative part of their business.

Since the failure of the VFT project there have periodic attempts to revive the concept. The latest was between 2010 and 2013 when the former Labor government produced a two-stage report on high-speed rail between Brisbane and Melbourne. It went nowhere.

In 2017 the Morrison/Turnbull government embarked on the latest attempt to explore either fast rail or high-speed rail by allocating $20m to fund business cases for such schemes.

They include studies for high-speed rail between Melbourne and Shepparton, which is being proposed by a private sector consortium, and two fast-rail projects: Sydney to Newcastle and Brisbane to the Sunshine Coast. The latter two have state involvement.

But there are question marks over the private consortium, Consolidated Land and Rail Australia, that won funding for the Melbourne-Shepparton business case and which has designs on a much grander plan: a high-speed line between Melbourne and Sydney funded by eight new cities along the route.

The federal government has given the consortium $8m towards development of the business case, although it has no shareholders with experience in construction of major projects.

Laird says the latest federal government initiative of seed funding is welcome, but more details are needed. The National Faster Rail agency was established on 1 July, but so far it has only an acting chief executive, Malcolm Southwell from the Department of Infrastructure. There is no expert committee yet, so no one is moving at high speed to get these projects rolling.

A piecemeal alternative

It may well be that states will drive the push to faster rail, if not high-speed rail.

Laird says Victoria is the most advanced, and there is a good case for pursuing the more modest goal, given the difficulties of making progress on high-speed rail.

“Australia could follow the lead of Germany and other countries in building isolated new sections of track to high-speed standards, one at a time. These sections can link with existing mainlines, to allow for new trains to run faster than cars,” he says.

This is the approach taken by Victoria, where some track can already run trains at 160km/h and more sections are planned.

During the federal election campaign the Coalition promised $2bn to upgrade the line between Melbourne and Geelong, which would cut the journey to just 32 minutes.

Scott Morrison said the project would take pressure off the Princes Freeway, which normally carries more than 54,000 vehicles a day.

Another $40m has been promised to fund businesses cases for five rail corridors, including Melbourne to Albury-Wodonga, and Melbourne to Traralgon in the Latrobe Valley.

NSW lags much further behind, although the premier, Gladys Berejiklian, says faster rail is now a priority.

Laird notes that it will be a much bigger and more expensive task for NSW. Many of its mainline tracks have “steam age” alignments with tight curves, making intercity train speeds much too slow without spending large sums to realign the tracks, he says.

The NSW government has retained Prof Andrew MacNaughton, who has worked on the UK’s hugely controversial HS2 project, to advise on options for high-speed rail or track upgrades to enable faster rail.

The study involves main lines from Sydney to Newcastle, Orange, Canberra and Wollongong.

A spokesman for Transport for NSW said the NSW government would prepare a high-level strategy this year and planning would take place over the next four years.

“A key consideration of the strategy is the development of a staged approach to ensure that each stage delivers immediate benefits while stepping closer to the game-changing vision,” a spokesperson said.

The federal government has chipped in with $5m towards the business case for the Newcastle line.

But these sums for business cases represent only the tiniest fraction of what needs to be spent to turn vision into reality.

Alexander says government will almost certainly need to play a role in the most ambitious projects, such as the Sydney – Canberra – Melbourne line.

“My view has always been: why wouldn’t you make it a giant public-private partnership?” he says.

Without a federal hand in driving progress, particularly towards a Sydney-Melbourne line, the very fast train has every chance of going metaphorically off the rails once again. A good start would be to reserve the critical rail corridors that will be needed for high-speed lines.

• Next: the former politicians who see profit in high-speed rail

View all comments >