Chinese people will make nearly 400 million train trips over Chinese new year (16 February this year). Migrant workers will leave the cities and head back to the countryside to see their children; students will travel home for the long winter holiday; elderly parents will visit their grown-up children.

The mass arrival of cars and planes has changed the nature of travel in China but the railways remain the country’s most important form of transport. However, trains do not just get you from A to B: in China, these often long journeys give travellers a snapshot of ordinary life, a sense of where they are.

On trains, I learned of the directness sometimes shown by Chinese people: once as I brushed my teeth in a washbasin at the end of a sleeping carriage, a man smoking a cigarette leaned over and tapped his ash into the bowl and, without explanation, walked away. On another trip, a 24-hour ride from Beijing to Hong Kong, I witnessed a little of Chinese people’s admirable patience with children: a group of fellow passengers whiled away many hours teaching card games to my young son. During the decade I lived in China, trains became my favourite way to travel. I crisscrossed the country for work and leisure, accompanied by family, friends and colleagues.

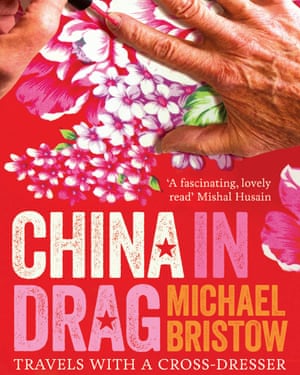

When I decided to write China in Drag: Travels with a Cross-Dresser, I took many rail journeys with my Chinese teacher, the cross-dresser in the title. Our trips didn’t only take me to the places I needed to go, they also gave me and the teacher plenty of time to solidify our friendship. We travelled to several places associated with his life story, and it was on one of these journeys that he finally revealed that he liked to wear women’s clothes. I stepped out of my hotel room one evening and saw him by the lift, dressed and made-up like a woman. I had known him for five years by then – he was nearly 60 – and had occasionally suspected that he had a secret he wanted me to know.

He would sometimes come to our lessons wearing what looked like lipstick or a delicate piece of jewellery. But he only felt confident enough to reveal his cross-dressing after he could be sure of our friendship – and when we were a long way from Beijing.

China’s rail network has gone through enormous changes over the past 10 years or so. The country has embarked on an ambitious government-funded project to connect all the country’s main cities with high-speed rail lines. These already cover more than 15,000 miles, and more track is planned in the coming years. The Chinese government has earmarked more than £80bn for high-speed rail construction this year alone. By comparison, in Britain there are still arguments about the £56bn HS2 rail project connecting north and south.

China’s communist leaders have always been willing to embark on massive infrastructure projects, and building these new lines has involved some remarkable feats of engineering. In December, a high-speed track opened between the cities of Xi’an, where the terracotta warriors are on show, and Chengdu, home of the pandas. Travelling at more than 150mph, trains use tunnels and bridges to navigate a formidable mountain range between the cities. It is a natural barrier that has hampered travel – and armies – for centuries.

Chinese high-speed trains now deliver passengers to their destinations far more quickly but there is still something to be said for taking a slower train. China is a continent-sized country, which means many of these slower engines need sleeping cars, and it is here that travellers often have their best opportunity to meet people and observe Chinese life. While researching modern China for my book, the teacher and I often took these less frenetic train journeys. It gave us ample time for conversation and allowed me to compare his views with those of other passengers.

On one trip – the overnight train from Beijing to Changsha – we fell into discussion with other travellers in our first-class compartment about Mao Zedong. We were off to see Mao’s hometown, just outside Changsha, and I wanted to know what people thought of the former leader. Shortly after Mao’s death in 1976, the Chinese Communist party came to the very precise conclusion that Mao was 70% right and 30% wrong. The party never revealed how it had arrived at this figure but it was a view endorsed by the restaurant owner sitting with us that evening.

“If Mao hadn’t unified the country, we wouldn’t have the progress we have today,” he said.

An overnight train also allows visitors a glimpse of the collectivist spirit that has not been extinguished in China, despite the capitalist economic reforms. Second-class sleeper carriages are a little like camping on iron wheels. In winter, passengers walk around in thermal underwear, not seeming to care they are in a public place. Compartments are separated by a simple partition wall. There is no door. In each compartment there are six beds, three on either side. The bunks are stacked on top of one another. There is little privacy and it is not unusual to find people sitting on your bed. In these circumstances, conversation seems almost preordained.

Occasionally, our rail trips would result in a comedy moment. We were travelling second class, in beds that faced each other, from Qiqihar in the north-east back to Beijing. When he awoke in the morning, the teacher was in a talkative mood and, as we lay there, he told a story about corruption from his time working in the propaganda department of a giant food company. The tale involved a former boss, who was worried he would be discovered driving a company car that was too luxurious for his rank. The teacher was dressed in what he had worn the previous evening, a tight T-shirt and what looked like a padded bra beneath. He found the story amusing and would occasionally break into fits of laughter, which became more frequent as he moved towards the conclusion of his tale.

As he laughed, a piece of flesh-coloured plastic started to push up out of the top of his T-shirt. I had no idea what it was and was wary of asking. The piece of plastic continued to work itself loose until, at one particularly funny moment in his story, it jumped out and fell on to the head of the man below, who was bending over a bowl of noodles. The teacher swooped down from his bunk and scooped up the piece of plastic, which I could now see was a fake breast. He quickly stuffed it back into his bra and carried on with his story as if nothing had happened.

That was not an everyday event but on my train travels I have seen a lot of Chinese life, on board and through the window. I have sat on hard, wooden seats that looked like church pews, shared my travelling space with chickens, and whooshed along at 200mph on a brand new high-speed train. Rail travel is not always the fastest but it is perhaps the most satisfying way to see China.

China in Drag, Travels with a Cross-Dresser (Sandstone Press, £8.99) by Michael Bristow is out now. To order a copy for £7.64 visit the guardian bookshop or call on 0330 333 6846

View all comments >