The life and death of reporter Michael Hastings has all the makings of a novel.

At 26, Hastings was covering the war in Iraq for Newsweek when he met and fell in love with Andrea Parhmamovich, an American teaching the Iraqis about democracy. After she was killed in an ambush, Hasting wrote his first book, I Lost My Love in Baghdad: A Modern War Story (2008).

In 2010, Hastings profiled Gen. Stanley McChrystal, the top U.S. commander in Afghanistan, revealing his contempt for President Obama and other civilian officials. Hastings' Rolling Stone article, "The Runaway General," was both widely praised and attacked. It ended McChrystal's military career.

Hastings expanded the article into his second book, The Operators, which was optioned as a movie. Brad Pitt plans to play McChrystal. Hastings has not yet been cast.

In 2013, 11 days after his article "Why the Democrats Love to Spy on Americans" was published by BuzzFeed, Hastings died in a lone-car crash in Los Angeles. He was 33.

His friends and colleagues later reported that Hastings believed he was being investigated by the FBI and in e-mails, and shortly before his death, wrote he was "onto a big story" and that he needed to "go off the radar."

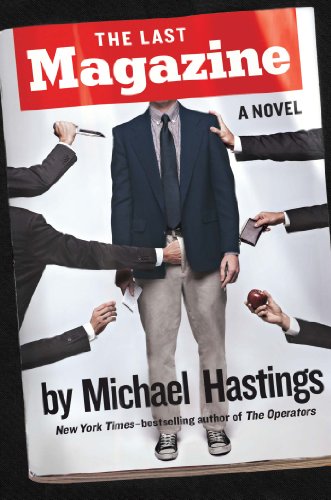

Now comes Hastings' first and only novel, The Last Magazine. It was found in his computer after his death.

It's a semi-autobiographical satire narrated by a smart, ironic young writer and fact-checker named Michael Hastings. He works at the New York offices of The Magazine, a fictional version of Newsweek. It's set mostly between 2002 and 2005, during the rush to war in Iraq. As in real life, the war is cheered, rather than questioned by much of the media.

The novel is raggedly uneven. It's insightful about the decline of print journalism and the rise of snarky websites. It features an entertaining gonzo war correspondent in a career and personal crisis and clueless editors interested only in their own careers and getting on TV. Hastings nails the emotional nature of TV when he writes, "Once you start trying to explain yourself on television, it's hard to win — you can't explain; you just have to state yourself, without hesitation."

But the novel also is also padded. There's a lot of crude sex and pornography, as if whenever the plot lagged, Hastings resorted to X-rated seasoning.

The young narrator comes to see the magazine's editors, along with most media executives, as "egotistical, vainglorious, pompous, insecure, corrupt." He goes on, "Not that they're bad people – they're not out there running death camps – but it's just who they are. If it weren't them, it's be someone else, right?''

As a satire, it's not in the same league as my favorite novels about the limits of journalism: Evelyn Waugh's Scoop (1938), Calvin Trillin's Floater (1980), and Tom Rachman's The Imperfectionists (2010).

But it has its moments. If journalism is best read as the first draft of history, then The Last Magazine can be read as a not-fully-polished draft of what Hastings might have done as a novelist. Sadly, it's also his last draft.

The Last Magazine

By Michael Hastings

Blue Rider, 336 pp.

3 stars out of four

Join the Nation's Conversation

To find out more about Facebook commenting please read the Conversation Guidelines and FAQs