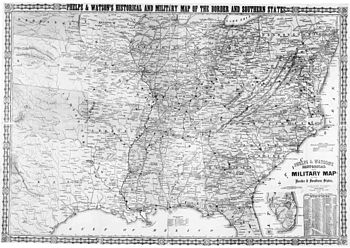

Border states (American Civil War)

In the context of the American Civil War, the term border states refers to slave states which did not declare their secession from the United States before April 1861. Four slave states never declared a secession: Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri, and four others did not declare secession until after the 1861 Battle of Fort Sumter: Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia — after which, they were less frequently called "border states". Also included as a border state during the war is West Virginia, which broke away from Confederate Virginia and became a new state in the Union.[1][2]

In all the border states there was a wide consensus against military coercion of the Confederacy. When Lincoln called for troops to march south to recapture Fort Sumter and other national possessions, local Unionists were dismayed, and secessionists in Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia were successful in getting those states to also declare independence from the U.S. and to join the Confederate States of America.[3]

In Kentucky and Missouri, there were both pro-Confederate and pro-Union governments. West Virginia was formed in 1862-63 from those northwestern counties of Virginia which had remained loyal to the Union and set up a loyalist ("restored") state government of Virginia. Though every slave state (except South Carolina) contributed some white troops to the Union as well as the Confederate side,[4][5] the split was most severe in these border states, with men from the same family often fighting on opposite sides.

With geographic, social, political, and economic connection to both the North and the South, the border states were critical to the outcome of the war, and still delineate the cultural border that separates the North from the South. Reconstruction, as directed by Congress, did not apply to the border states, because they never left the union. They did undergo their own process of readjustment and political realignment, which somewhat resembled the reconstruction of the ex-Confederate states. After 1880 most adopted the Jim Crow system of segregation and second-class citizenship for blacks, although they were still allowed to vote.[6]

Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to the border states. Missouri, Maryland, and West Virginia all abolished slavery during the war. In Kentucky and Delaware, the 40,000 or so remaining slaves were emancipated by the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865.

Contents |

[edit] Background

In the Border states, slavery was systematically dying out in the urban areas and the regions without cotton, especially in cities that were rapidly industrializing, such as Baltimore, Louisville, and St. Louis.[7] However, there was still profit to be made by selling slaves to the cotton plantations in the deep South, as cotton was very profitable and the price of prime field hands kept rising.[8] In contrast to the unanimity of the seven cotton states in the lower South, the border slave states were bitterly divided about secession and were not eager to leave the Union. Border Unionists hoped that some compromise would be reached and they assumed that Lincoln would not send an army. Border secessionists paid less attention to the slavery issue in 1861; their states' economies were based more on trade with the North than on cotton and they lacked the South Carolinian dream of a slave-based empire oriented south toward the Caribbean. Rather their main focus in 1861 was on coercion: Lincoln's call to arms seemed a repudiation of the American traditions of states rights, democracy, liberty, and a republican form of government. The disunionists insisted that Washington had usurped illegitimate powers in defiance of the Constitution, and thereby had lost its legitimacy.[3] After Lincoln called for troops, Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina promptly declared their secessions and joined the Confederacy, but a secession movement began in western Virginia to break away and remain in the Union.[9]

Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland, with much stronger ties to the North than to the South, were deeply divided; Kentucky tried to proclaim itself neutral. Union military forces were used to guarantee these states remained in the Union. The western counties of Virginia rejected secession, set up a loyal government of Virginia (with representation in the U.S. Congress), and created the new state of West Virginia.[9]

[edit] The five border states

Each of these five states shared a border with the free states and were aligned with the Union. All but Delaware also share borders with states that joined the Confederacy.

[edit] Delaware

Both houses of Delaware's General Assembly rejected secession overwhelmingly, the House of Representatives unanimously.

[edit] Maryland

Union troops had to go through Maryland to reach the national capital at Washington DC. Had Maryland also joined the Confederacy, Washington DC would have been totally surrounded. The Maryland Legislature rejected secession in 1861, and Governor Thomas Hicks voted against it. As a result of the Union Army's heavy presence in the state and the suspension of habeas corpus, several Maryland state legislators, as well as officials in Baltimore and other outspoken secessionists were arrested and briefly imprisoned.Maryland contributed troops to both the Union (60,000), and the Confederate (25,000) armies.

Maryland adopted a new state constitution in 1864, which prohibited slavery and thus emancipated all slaves in the state.

[edit] Kentucky

Kentucky was strategic to Union victory in the Civil War. Lincoln once said, "I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we cannot hold Missouri, nor Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capital"[10] (Washington, which was surrounded by slave states: Confederate Virginia and Union-controlled Maryland). He is further reported to have said that he hoped to have God on his side, but he had to have Kentucky.

Kentucky did not secede, but a faction, known as the Russellville Convention, formed a Confederate government of Kentucky, which was recognized by the Confederate States of America as a member state. Kentucky was represented by the central star on the Confederate battle flag.[11]

Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin proposed that slave states like Kentucky should conform to the US Constitution, and remain in the Union. When Lincoln requested 75,000 men to serve in the Union army, however, Magoffin, a Southern sympathizer, countered that Kentucky would "furnish no troops for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister Southern states."

Kentucky tried to remain neutral, even issuing a proclamation May 20, 1861, asking both sides to keep out. The neutrality was broken when Confederate General Leonidas Polk occupied Columbus, Kentucky, in the summer of 1861, though the Union had been openly enlisting troops in the state before this. In response, the Kentucky Legislature passed a resolution directing the governor to demand the evacuation of Confederate forces from Kentucky soil. Magoffin vetoed the proclamation, but the legislature overrode his veto. The legislature further decided to back General Ulysses S. Grant, and his Union troops stationed in Paducah, Kentucky, on the grounds that the Confederacy voided the original pledge by entering Kentucky first.

Southern sympathizers were outraged at the legislature's decisions, citing that Polk's troops in Kentucky were only en route to countering Grant's forces. Later legislative resolutions—such as inviting Union General Robert Anderson to enroll volunteers to expel the Confederate forces, requesting the governor to call out the militia, and appointing Union General Thomas L. Crittenden in command of Kentucky forces—only incensed the Southerners further. (Magoffin vetoed the resolutions but all were overridden.) In 1862, the legislature passed an act to disenfranchise citizens who enlisted in the Confederate States Army. Thus Kentucky's neutral status evolved into backing the Union. Most of those who originally sought neutrality turned to the Union cause.

When Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston occupied Bowling Green, Kentucky in the summer of 1861, the pro-Confederates in western and central Kentucky moved to establish a Confederate state government. The Russellville Convention met in Logan County on November 18, 1861. One hundred sixteen delegates from 68 counties elected to depose the current government, and create a provisional government loyal to Kentucky's new unofficial Confederate Governor George W. Johnson. On December 10, 1861, Kentucky became the 13th state admitted to the Confederacy. Kentucky, along with Missouri, was a state with representatives in both Congresses, and with regiments in both Union and Confederate armies.

Magoffin, still functioning as official governor in Frankfort, would not recognize the Kentucky Confederates, nor their attempts to establish a government in his state. He continued to declare Kentucky's official status in the war was as a neutral state—even though the legislature backed the Union. Magoffin, fed up with the party divisions within the population and legislature, announced a special session of the legislature, and then resigned his office in 1862.

Bowling Green remained occupied by the Confederates until February 1862, when General Grant moved from Missouri, through Kentucky, along the Tennessee line. Confederate Governor Johnson fled Bowling Green with the Confederate state records, headed south, and joined Confederate forces in Tennessee. After Johnson was killed fighting in the Battle of Shiloh, Richard Hawes was named Confederate governor. Shortly afterwards, the Provisional Confederate Congress was adjourned on February 17, 1862, on the eve of inauguration of a permanent Congress. However, as Union occupation henceforth dominated the state, the Kentucky Confederate government, as of 1863, existed only on paper, and its representation in the permanent congress was minimal. It was dissolved when the Civil War ended in the spring of 1865.

[edit] Missouri

After the secession of Southern states began, the newly elected governor of Missouri called upon the legislature to authorize a state constitutional convention on secession. A special election approved of the convention, and delegates to it. This Missouri Constitutional Convention voted to remain within the Union, but rejected coercion of the Southern States by the United States. Pro-Southern Governor Claiborne F. Jackson was disappointed with the outcome. He called up the state militia to their districts for annual training. Jackson had designs on the St. Louis Arsenal, and had been in secret correspondence with Confederate President Jefferson Davis, to obtain artillery for the militia in St. Louis. Aware of these developments, Union Captain Nathaniel Lyon struck first, encircling the camp, and forcing the state militia to surrender. While marching the prisoners to the arsenal, a deadly riot erupted (the Camp Jackson Affair.)

These events caused greater Confederate support within the state. The already pro-Southern legislature passed the governor's military bill creating the Missouri State Guard. Governor Jackson appointed Sterling Price, who had been president of the convention, as major general of this reformed and expanded militia. Price, and Union district commander Harney, came to an agreement known as the Price-Harney Truce, that calmed tensions in the state for several weeks. After Harney was removed, and Lyon placed in charge, a meeting was held in St. Louis at the Planters' House between Lyon, his political ally Francis P. Blair, Jr., Price, and Jackson. The negotiations went nowhere, and after a few fruitless hours Lyon made his famous declaration, "this means war!" Price and Jackson rapidly departed for the capital.

Jackson, Price, and the state legislature, were forced to flee the state capital of Jefferson City on June 14, 1861, in the face of Lyon's rapid advance against the state government. In the absence of the now exiled state government, the Missouri Constitutional Convention reconvened in late July. On July 30, the convention declared the state offices vacant, and appointed a new provisional government with Hamilton Gamble as governor. President Lincoln's Administration immediately recognized the legitimacy of Gamble's government, which provided both pro-Union militia forces for service within the state, and volunteer regiments for the Union Army.

Fighting ensued between Union forces, and a combined army of General Price's Missouri State Guard and Confederate troops from Arkansas and Texas, under General Ben McCulloch. After winning victories at the battle of Wilson's Creek, and the siege of Lexington, Missouri, the secessionist forces had little choice but to retreat again to Southwestern Missouri, as Union reinforcements arrived. There, on October 30, 1861 in the town of Neosho, Jackson called the exiled state legislature into session, where they enacted a secession ordinance. It was recognized by the Confederate congress, and Missouri was admitted into the Confederacy on November 28.

The exiled state government was forced to withdraw into Arkansas. for the rest of the war, it consisted of several wagon loads of civilian politicians attached to various Confederate armies. In 1865, it vanished. Regular Confederate troops staged several large-scale raids into Missouri, but most of the fighting in the state for the next three years consisted of guerrilla warfare. The guerrillas were primarily Southern partisans, including William Quantrill, Frank and Jesse James, the Younger brothers, and William T. Anderson. Such small unit tactics pioneered by the Missouri Partisan Rangers were seen in other occupied portions of the Confederacy during the Civil War. The James' brothers outlawry after the war has been seen as a continuation of guerrilla warfare.

The Union response was to suppress the guerrillas. It did that in western Missouri by concentrating the pro-Confederate civilians into heavily guarded camps, and declare the open country a free-fire zone. Union cavalry units would identify and track down scattered Confederate remnants, who had no places to hide and no secret supply bases. Thereby, Missouri came under the control of the Union government.[12]

[edit] West Virginia

[edit] Background

The serious divisions between the western and eastern sections of Virginia did not begin in the winter of 1860-1861. West Virginia historian C. H. Ambler wrote that “there are few years during the period from 1830 to 1850 which did not bring forth schemes for the dismemberment of the commonwealth.” The western part of the state during this time was “the growing and aggressive section,” while the east was “the declining and conservative one.” The west centered its grievances on the east’s disproportionate (based on population) legislative representation, and share of state revenues. The east justified this dominance because of its dependence on slaves, “the possession of which could be guaranteed and secured only by giving to masters a voice in the government adequate to the protection of their interests.”[13] In 1851, the Virginia Reform Convention, forced to recognize that the White population of the western part of the state outnumbered the east, made significant changes. Universal white suffrage was granted, and the governor was to be determined by the direct vote of the people. The lower house of the legislature was apportioned strictly based on population, although the upper house still used a combination of population and property in determining its electoral districts.[14]

By 1859 there were again strong sectional tensions at work within the state, although the west itself was split between the north and the south, with the south more satisfied with the changes made in 1851. Historian Daniel W. Crofts wrote, “Northwesterners complained that they had become ‘the complete vassals of Eastern Virginia,’ taxed ‘unmercifully and increasingly, at her instance and for her benefit.’” Internal improvements important to the west, such as the James River and Kanawha Canal, or railroads connecting the west to the east, had been promised but not built. Slaves, for tax purposes, were not valued above $300, despite a top field hand being worth five times that amount.[15] The west had 135,000 more whites than the east, but the east controlled the state Senate. In the United States House of Representatives, because of the three-fifth rule, only five of Virginia’s thirteen representatives came from western districts.[16] In the 1859 gubernatorial elections there was disenchantment with both parties in the west. Western grievances were ignored as “both parties engaged in a proslavery shouting match.” Antislavery Whigs began to move towards the Republican Party; in the 1860 presidential election, Abraham Lincoln received 2,000 votes from the western panhandle.[17]

Crofts wrote that “no document better captures the mood of unconditional northwestern Virginia Unionists” than the following from a March 16, 1861 letter by Henry Dering of Morgantown to Waitman T. Willey:

Talk about Northern oppression, talk about our rights being stolen from us by the North – it’s all stuff, and dwindles into nothing when compared, to our situation in Western Virginia. The truth is the slavery oligarchy, are impudent boastful and tyrannical, it is the nature of the institution to make men so – and tho I am far, from being an abolitionist, yet if they persist, in their course, the day may come, when all Western Virginia will rise up, in her might and throw off the Shackles, which thro this very Divine institution, as they call it, has been pressing us down.[18]

[edit] Virginia’s secession and western reaction

By December 1860 secession was being publicly debated throughout Virginia. Leading eastern newspapers such as the Richmond Inquirer, Richmond Examiner, and Norfolk Argus were openly calling for secession.[19] The Wellsburg Herald on December 14 warned the east that the west would not be “legislated into treason or dragged into trouble to gratify the wishes of any set of men, or to subserve the interests of any section.”[20] The Morgantown Star on January 12 said that their region was “unwilling that slavery in Virginia shall be used to oppress the people of our section of the state. ... We people in Western Virginia have borne the burden just about as long as we can stand it. We have been ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’ for Eastern Virginia long enough.”[21] In addition to traditional east- west differences, the specter of secession raised new issues for the northwest. This section[22] shared a 450-mile (720 km) border with Ohio and Pennsylvania and, by virtue of the state’s failure to build roads, was isolated from the rest of the state. A leading unionist said, “We would be swept by the enemy from the face of the earth before the news of the attack could reach our Eastern friends.” Another unionist, addressing the section’s close economic links with the North, asked, “Would you have us ... act like madmen and cut our own throats merely to sustain you in a most unwarrantable rebellion.”[23]

Despite unionist opposition, a special session of the state legislature in early January called for the election of delegates to a state convention on February 4 to consider secession. A proposal by Waitman T. Willey to have the convention also consider reforms to taxation and representation went nowhere.[24] After the ordinance was passed by the convention Chester T. Hubard wrote to Willey, “I should like to show those traitors at Richmond ... that we are not to be transformed like the cattle on the hills or the slaves on their plantations, without our knowledge or consent.” [25] The convention first met on February 13 and voted for secession on April 17, 1861. The decision was dependent on ratification by a statewide referendum.

On April 22, 1861 John S. Carlisle led a meeting of 1,200 people in Harrison County. The meeting approved the “Clarksburg Resolutions”, calling for the creation of a new state separate from Virginia. The resolutions were widely circulated and each county was asked to choose five “of their wisest, best, and distinguished men” as delegates.[26] Historian Allan Nevins wrote, “ The movement, spontaneous, full of extralegal irregularities, and varying from place to place, spread like the wind. Community after community held mass meetings.”[27]

Unionists in Virginia met at the Wheeling Convention from May 13 to May 15 to await the decision of the state referendum called to ratify the decision to secede.[28] In attendance were over four hundred delegates from twenty-seven counties. Most delegations were chosen by public meetings rather than elections and some attendees came strictly on their own. The editor of the Wheeling Western Star called it “almost a mass meeting of the people instead of a representative body.”[29]

Carlisle, in front of a banner proclaiming “New Virginia, now or never”, spoke for the immediate creation of a new state consisting of thirty-two counties. Speaking of the actions of the Virginia secession convention, he said, “Let us act; let us repudiate these monstrous usurpations; let us show our loyalty to Virginia and the Union at every hazard. It is useless to cry peace when there is no peace; and I for one will repeat what was said by one of Virginia’s noblest sons and greatest statesmen, ‘Give me liberty or give me death.’[30]

Speaking in opposition to action at this time, Willey argued that the convention had no authority to take such an action and referred to it as “triple treason”. Francis H. Pierpont supported Willey and helped to work out a compromise that secured the withdrawal of the Carlisle motion, declared the state’s Ordinance of Secession to be “unconstitutional, null, and void", and called for a second convention on June 11 if secession was ratified.[31]

Willey’s closing remarks to the convention set the stage for the June meeting:

Fellow citizens, the first thing we have got to fight is the Ordinance of Secession. Let us kill it on the 23rd of this month. Let us bury it deep within the hills of Northwestern Virginia. Let us pile up our glorious hills on it; bury it deep so that it will never make its appearance among us again. Let us go back home and vote, even if we are beaten upon the final result, for the benefit of the moral influence of that vote. If we give something like a decided ... majority in the Northwest, that alone secures our rights. That alone, at least secures at independent State if we desire it.[32]

[edit] Second Wheeling Convention

The statewide vote in favor of secession was 132,201 to 37,451. In the core Unionist region of northwestern Virginia the vote was 30,586 to 10,021 against secession, although the total vote in the counties that would become West Virginia was a closer 34,677 to 19,121 against.[33] Other sources give the total vote as 125,950 in favor and 20,373 against, with many ballots in western Virginia not being counted.[34]

The Second Wheeling Convention opened on June 11 with more than 100 delegates from 32 western counties representing nearly one-third of Virginia’s total voting population. Members of the Virginia General Assembly were accepted as long as they were loyal to the Union[35] "and still others were seemingly self-appointed."[36] The convention met in open defiance of the Richmond authorities and Confederates tried to restrict attendance.

Arthur I. Boreman, the future governor of West Virginia, was chosen as president, but the main leaders were Carlisle and Frank Pierpont. While many still supported Carlisle’s original plan to create a new state, Article IV Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution presented a problem. This section guaranteed that “no new states shall be formed or erected within the jurisdiction of any other state... without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States Concerned as well as of Congress." The solution was to create a new Virginia government that Washington would recognize. All state offices would be declared vacant (since they were held by men who had disavowed allegiance to the United States), and be replaced by Union men. This restored Virginia government then would approve the creation of a new state within Virginia's old borders.

On June 13 Carlisle presented his “Declaration of Rights of the People of Virginia” to the convention. It accused the secessionists of “usurping” the rights of the people, creating an “illegal confederacy of rebellious states”, and declared it was now their duty “to abolish” the state government as it existed. The convention approved this declaration on June 17 by a 56 to 0 vote. On June 14 “An Ordinance for the Re-organization of the State Government” was presented which provided for the selection of a governor, lieutenant governor, and a five-member governor’s council by the convention, declared all state government offices vacant, and recognized a “rump legislature” composed of loyal members of the General Assembly who had been elected in the May 23 statewide voting. This ordinance was approved on June 19.[37]

Francis H. Pierpont was chosen as governor of Virginia (not West Virginia) on June 20. The next day Governor Pierpont notified President Lincoln of the convention’s decisions. Noting that there were “evil-minded persons” who were “making war on the loyal people of the state” and “pressing citizens against their consent into their military organization and seizing and appropriating their property to aid in the rebellion,” Pierpont requested aid “to suppress such rebellion and violence.”[38] Secretary of War Cameron, replying for Lincoln, wrote:

The President ... never supposed that a brave and free people, though surprised and unarmed, could long be subjugated by a class of political adventurers always adverse to them, and the fact that they have already rallied, reorganized their government, and checked the march of these invaders demonstrates how justly he appreciated them.[39]

[edit] "Restored" Virginia and dismemberment

The Restored Government of Virginia granted permission for the formation of a new state on August 20, 1861. The Lt. Governor of the Restored Government, Daniel Polsley, strongly objected to the ordinance for the new state, saying in a speech on August 16:

If they proceeded now to direct a division of the State before a free expression on the people could be had, they would do a more despotic act than any done by the Richmond Convention itself...They now proposed a division when it was impossible for one-fourth of even the counties included in the boundaries proposed to give even an expression upon the proposition.[40]

The October 24, 1861 popular vote on the new state drew only 19,000 voters (compared to the 54,000 who had voted in the original secession referendum).

The Second Wheeling Convention had proposed that only 39 counties be included in the new state. This number included 24 anti-secession counties and 15 secessionist counties which the new state would find “imperative” because of their geographic relationship with the rest of the new state. These 39 counties contained a white population of 272,759, 78% of whom had a Unionist orientation.[41] While there was overwhelming support at this convention for statehood, there was a “small, effective minority” that opposed this and they used “obstructionist tactics at every opportunity” in their efforts to defeat the majority. It was this group opposed to statehood that was largely responsible for the inclusion of additional counties beyond this core.[42]

When the constitutional convention was held in Wheeling on November 16, 1861, the obstructionists attempted to have 71 counties included in the new state, a move which would have created a white confederate sympathizer majority of 316,308. Eventually a compromise was worked out to include 50 counties.[43] Historian Richard O. Curry summed the results up this way:

In conclusion, then, twenty-five of fifty counties encompassed by West Virginia supported the Confederacy and opposed dismemberment. The Rebel minority ran as high as 40 per cent in a few Union counties but the reverse was also true. Therefore, because northwestern Union counties contained 60 percent of the total population and the Confederate counties 40 per cent, a 60-40 ration, the majority being Unionists, would appear to be a fair estimate of the division of sentiment among the inhabitants included in the state of West Virginia.[42]

Curry further concluded:

On the other hand – and this is important too – the West Virginia government did not coerce the unwilling counties of the Valley and the southwest; it made little or no attempt to exercise effective control over these Confederate counties until after the war. Never at any time during the war did the Pierpont government or the administration of Arthur I. Boreman, first governor of West Virginia, control more than half the counties in the state.[44]

The new state constitution was passed by the Unionist counties in the spring of 1862 and this was approved by the restored Virginia government in May 1862. The statehood bill for West Virginia was passed by Congress in December and signed by President Lincoln on December 31, 1862.[44] As a condition for statehood the US Congress required that a policy of gradual emancipation be granted to the slaves of the new state, called the Willey Amendment, which was amended to the state constitution on March 26, 1863.

[edit] Military decisions

The ultimate decision about West Virginia was made by the armies in the field; the Confederates were defeated, the Union was triumphant, so West Virginia was born. In late spring 1861 Union troops from Ohio moved into western Virginia with the primary strategic goal of protecting the B & O Railroad. General George B. McClellan in June 3 at Philippi, July 11 at Rich Mountain, and September 10 at Carnifex Ferry “completely destroyed Confederate defenses in western Virginia.”[45] However after these victories most Federal troops were sent out of the new state to support McClellan elsewhere, leading Governor Boreman to write from Parkersburg "The whole country South and East of us is abandoned to the Southern Confederacy."[46] In central, southern and eastern West Virginia a guerrilla war ensued that lasted until 1865.[47] Raids and recruitment by the Confederacy took place throughout the war.

[edit] Other issues

[edit] Tennessee

Though Tennessee had officially seceded, East Tennessee was pro-Union and had mostly voted against secession. Attempts to secede from Tennessee were suppressed by the Confederacy. Jefferson Davis arrested over 3,000 men suspected of being loyal to the Union and held them without trial.[48] Tennessee came under control of Union forces in 1862 and was omitted from the Emancipation Proclamation. After the war, Tennessee was the first state to have its elected members readmitted to the US Congress.

[edit] Alabama

Winston County, Alabama, issued a resolution of secession from the state of Alabama.

[edit] Oklahoma

In the Indian Territory (now the state of Oklahoma), most Indian Tribes owned black slaves, and sided with the Confederacy. However, some tribes sided with the Union, and a bloody civil war resulted in the territory.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- Ambler, Charles H. "The Cleavage between Eastern and Western Virginia". The American Historical Review Vol. 15, No. 4, (July 1910) pp. 762–780 in JSTOR

- Ash. Steven V. Middle Tennessee Transformed, 1860-1870 Louisiana State University Press, 1988.

- Baker, Jean H. The Politics of Continuity: Maryland Political Parties from 1858 to 1870 Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

- Brownlee, Richard S. Gray Ghosts of the Confederacy: Guerrilla Warfare in the West, 1861-1865 (1958).

- Coulter, E. Merton. The Civil War and Readjustment in Kentucky University of North Carolina Press, 1926.

- Crofts, Daniel W. Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis. (1989).

- Current, Richard Nelson. Lincoln's Loyalists: Union Soldiers From the Confederacy. (1992).

- Curry, Richard O. A House Divided: A Study of Statehood Politics and the Copperhead Movement in West Virginia. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1964.

- Curry, Richard O. "A Reappraisal of Statehood Politics in West Virginia". The Journal of Southern History Vol. 28, No. 4. (November, 1962) pp. 403–421. in JSTOR

- Fellman, Michael. Inside War. The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri during the American Civil War (1989).

- Fields, Barbara. Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century (1987).

- Gilmore, Donald L. Civil War on the Missouri-Kansas Border (2005)

- Hancock Harold. Delaware during the Civil War. Historical Society of Delaware, 1961.

- Harrison, Lowell. The Civil War in Kentucky University Press of Kentucky, 1975.

- Josephy, Alvin M. Jr., The Civil War in the American West. 1991.

- Kerby, Robert L. Kirby Smith's Confederacy: The Trans-Mississippi South, 1863-1865 Columbia University Press, 1972.

- Link, William A. Roots of Secession: Slavery and Politics in Antebellum Virginia. (2003)

- Lesser, W. Hunter. Rebels at the Gate: Lee and McClellan at the Front Line of a Nation Divided. (2004)

- Maslowski Peter. Treason Must Be Made Odious: Military Occupation and Wartime Reconstruction in Nashville, Tennessee, 1862-65 1978.

- McGehee, C. Stuart. "The Tarnished Thirty-fifth Star" in Virginia at War: 1861. Davis William C. and Robertson, James I. Jr. (2005).

- Monaghan, Jay. Civil War on the Western Border, 1854-1865 (1955)

- Moore, George E. A Banner in the Hills: West Virginia's Statehood (1963)

- Nevins, Allan. The War for the Union: The Improvised War 1861-1862. (1959).

- Parrish, William E. Turbulent Partnership: Missouri and the Union, 1861-1865 University of Missouri Press, 1963.

- Patton, James W. Unionism and Reconstruction in Tennessee, 1860-1867 University of North Carolina Press, 1934.

- Rampp, Lary C., and Donald L. Rampp. The Civil War in the Indian Territory. Austin: Presidial Press, 1975.

- Sheeler, J. Reuben. "Secession and The Unionist Revolt," Journal of Negro History, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Apr., 1944), pp. 175–185 in JSTOR, covers east Tennessee

- Stiles, T.J. "Jesse James: The Last Rebel of the Civil War". Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

[edit] Footnotes

- ^ Maury Klein, Days of Defiance: Sumter, Secession, and the Coming of the Civil War (Knopf, 1997) p 22

- ^ "From February into the late spring, North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and Arkansas were considered border states" says David Stephen Heidler et al, eds. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War (2002) p. 252

- ^ a b Daniel W. Crofts, Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis (1989)

- ^ History of the 1st Alabama Cavalry, USV

- ^ World History Blog: Pro-Union Southerners

- ^ Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, by Mary L. Hart, Charles Reagan Wilson, William Ferris and Ann J. Adadie, Univ. of N. Carolina Press, 1989. ISBN 0807818232

- ^ In nine of the ten chief southern cities, the proportion of slaves steadily declined before the war. The exception was Richmond, Virginia. Midori Takagi, "Rearing Wolves to Our Own Destruction": Slavery in Richmond, Virginia, 1782-1865 (University Press of Virginia, 1999) p 78.

- ^ Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861 (1950) pages 149-55

- ^ a b Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861 (1950) pages 119-47

- ^ Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Volume 4 page 533 Roy P. Basler

- ^ Irby, Jr., Richard E.. "A Concise History of the Flags of the Confederate States of America and the Sovereign State of Georgia". About North Georgia. Golden Ink. http://ngeorgia.com/history/flagsofga.html. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ^ William E. Parrish, Turbulent Partnership: Missouri and the Union, 1861-1865 (1963)

- ^ Ambler (1910) pp. 764-765

- ^ Crofts pp. 57-58

- ^ Crofts p. 159. The only railroad in the area, the B & O, had been built without state money. Slaves under age 12 were not taxed at all.

- ^ Nevins p. 140. Nevins also wrote, “... according to Francis H. Pierpont, the principal western leader, each year [the east] escaped paying $900,000 in taxes justly its due” and “all of the $30,000,000 by which the State debt had been augmented since 1851 had gone for internal improvements in the east.”

- ^ Croft pp. 59, 160. Ambler p. 779. Ambler wrote f the state Republican platform drafted in Wheeling in the spring of 1860, “It also alleged that the slave interests of Virginia had encroached upon the personal rights of the free white men of her western counties by weighing them down with oppressive taxation and by denying them a proportionate representation in the general assembly.”

- ^ Crofts p. 163

- ^ Croft p. 102

- ^ Link p. 250

- ^ Crofts p. 162

- ^ Curry “A Reappraisal of Statehood Politics in West Virginia” p. 404. Throughout this article the term “northwest” refers to a section made up of 35 counties, only twenty four of which had significant unionist strongholds

- ^ Crofts p. 160

- ^ Crofts p. 161.

- ^ Curry “A Reappraisal of Statehood Politics in West Virginia”, p. 406

- ^ Curry “A Reappraisal of Statehood Politics in West Virginia”, p. 406. Lesser pp. 25-26.

- ^ Nevins p. 141

- ^ Link p. 251

- ^ Lesser p. 26. Curry p. 406

- ^ Lesser p. 27

- ^ Lesser pp. 28-29. “Triple treason” referred to, in Lesser’s paraphrasing, “treason against the State of Virginia, treason against the U. S. Constitution, even treason against Virginia’s alliance with the Confederacy.”

- ^ Lesser p. 30

- ^ Crofts p. 341

- ^ "Chapter Six: Ratification of the Ordinance of Secession". http://www.wvculture.org/History/statehood/statehood06.html.

- ^ Lesser p. 77

- ^ Ambler, "The History of West Virginia", p. 318

- ^ Lesser pp. 78-79

- ^ Current p. 15

- ^ Current pp. 15-16

- ^ Lewis, "How West Virginia Was Made", p. 230

- ^ Curry “A Reappraisal of Statehood Politics in West Virginia" p. 417

- ^ a b Curry “A Reappraisal of Statehood Politics in West Virginia” p. 412

- ^ Curry “A Reappraisal of Statehood Politics in West Virginia” pp. 417-418

- ^ a b Curry “A Reappraisal of Statehood Politics in West Virginia” p. 407

- ^ McGehee p. 149

- ^ Curry, "A House Divided", p. 77

- ^ "Exterminating Savages", by Kenneth W. Noe, in "The Civil War in Appalachia", pp. 104-130

- ^ Mark Neely, Confederate Bastille: Jefferson Davis and Civil Liberties 1993 pp. 10–11

[edit] External links

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Border States

- Thomas, William G., III. "The Border South." Southern Spaces, April 16, 2004, http://southernspaces.org/2004/border-south.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||